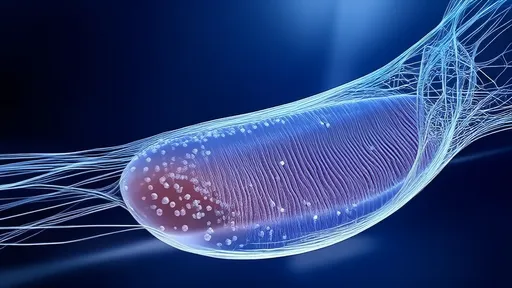

In a groundbreaking development that merges biotechnology with ophthalmology, scientists have successfully engineered artificial corneas using transgenic spider silk proteins derived from silkworms. This innovation promises to revolutionize corneal transplantation, offering hope to millions suffering from corneal blindness worldwide. Unlike traditional donor-dependent procedures, this bioengineered solution leverages nature’s strongest fiber—spider silk—reimagined through genetic modification.

The cornea, the eye’s transparent outer layer, is essential for vision. Damage or disease to this delicate tissue can lead to blindness if left untreated. While human donor corneas remain the gold standard for transplants, severe shortages and rejection risks persist. Enter spider silk: a material renowned for its strength, flexibility, and biocompatibility. By harnessing silk proteins from genetically modified silkworms, researchers have created a scaffold that mimics the human cornea’s structural integrity while minimizing immune rejection.

How It Works: From Silkworms to Sight Restoration

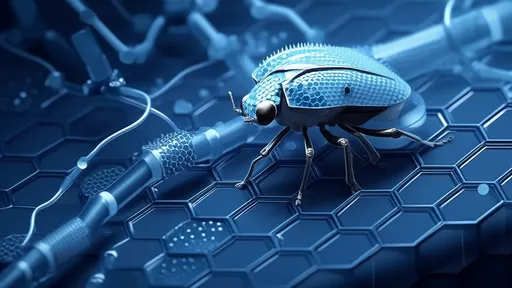

The process begins with silkworms genetically altered to produce spider silk proteins. Unlike spiders, which are notoriously difficult to farm, silkworms are easily cultivated and produce large quantities of silk. Through CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology, scientists inserted spider silk genes into silkworms, resulting in fibers that combine the best of both worlds: the mass-production capability of silkworms and the unparalleled properties of spider silk.

Once harvested, these transgenic silk fibers are purified and processed into a transparent, hydrogel-like film. This film serves as the foundation for the artificial cornea, engineered to match the curvature and optical clarity of a natural cornea. Early trials show the material integrates seamlessly with human eye tissue, promoting cell growth and nerve regeneration—a critical factor for restoring vision.

Advantages Over Conventional Methods

Traditional corneal transplants rely on cadaveric donors, a system plagued by logistical and ethical challenges. Donor corneas must be used within weeks, and recipients often face lifelong immunosuppressive therapy to prevent rejection. The spider silk-based cornea, however, is shelf-stable for months and elicits minimal immune response due to its biocompatible nature. This could democratize access to corneal replacements, particularly in low-resource regions where donor tissue is scarce.

Another leap forward is the material’s ability to self-assemble at the molecular level, reducing manufacturing complexity. Unlike synthetic polymers, which may degrade unpredictably, silk proteins break down into harmless amino acids, leaving no toxic residues. This biodegradability, paired with its optical precision, positions spider silk as an ideal candidate for not just corneas but other biomedical applications like skin grafts or drug delivery systems.

Clinical Trials and Future Prospects

Preliminary animal studies have yielded promising results. Rabbits implanted with the silk-based corneas showed significant visual improvement within weeks, with no signs of inflammation or rejection. Human trials are slated to begin within two years, pending regulatory approvals. If successful, this technology could enter mainstream medicine by the decade’s end.

Looking ahead, researchers aim to refine the material’s refractive properties to correct vision defects like astigmatism. Some teams are even exploring “smart” corneas embedded with nanosensors to monitor intraocular pressure—a game-changer for glaucoma patients. The potential extends beyond ophthalmology; the same silk scaffolds could pioneer advances in neural tissue engineering or even wearable electronics.

Ethical and Environmental Considerations

While the science is transformative, it’s not without controversy. Genetic modification of organisms, even for medical purposes, raises ethical questions. Critics argue that manipulating silkworms’ DNA could have unforeseen ecological impacts if genetically altered insects were to escape controlled environments. Proponents counter that the benefits—saving sight and reducing animal testing (no spiders are harmed)—outweigh hypothetical risks.

Moreover, the production process is remarkably sustainable. Silkworms require minimal resources compared to synthetic material factories, and their silk is biodegradable. This aligns with global pushes for greener medical technologies. As Dr. Elena Petrov, a lead researcher on the project, notes, “We’re not just rebuilding vision; we’re redefining medical manufacturing with nature as our blueprint.”

The spider silk artificial cornea exemplifies how ancient materials, when paired with cutting-edge science, can solve modern crises. For the 12.7 million people awaiting corneal transplants worldwide, this innovation isn’t just progress—it’s light at the end of a very long tunnel.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025