The early detection of Parkinson’s disease has long been a challenge for clinicians, but recent advances in neurodiagnostic tools are offering new hope. Among these, eye-tracking technology has emerged as a promising method for identifying early markers of the disease. Unlike traditional diagnostic approaches that rely on motor symptoms—which often appear only after significant neurodegeneration has occurred—eye movement analysis provides a window into the subtle neurological changes that precede overt physical manifestations.

Researchers have discovered that specific eye movement abnormalities correlate with the early stages of Parkinson’s. These include impairments in saccadic movements (rapid shifts of gaze), smooth pursuit tracking (following a moving object), and fixation stability (maintaining focus on a stationary target). What makes these findings particularly compelling is that they can be detected before patients exhibit the classic tremors or rigidity associated with the disease. This non-invasive, cost-effective approach could revolutionize how we diagnose and monitor Parkinson’s, enabling earlier interventions that may slow disease progression.

The Science Behind Eye Movement and Parkinson’s

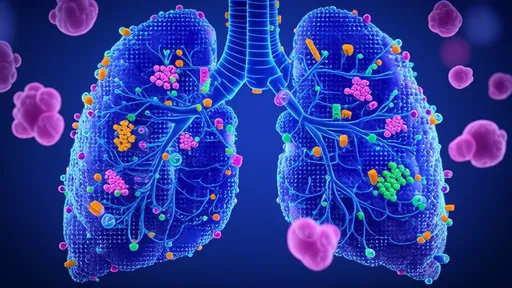

At the heart of this breakthrough is the understanding that Parkinson’s disease affects not just the motor cortex but also the brainstem and basal ganglia—regions critical for controlling eye movements. The substantia nigra, a key area damaged in Parkinson’s, plays a role in coordinating voluntary eye movements through its connections with the superior colliculus. As dopamine-producing neurons degenerate, the precision and timing of eye movements deteriorate, creating measurable patterns that differ from those seen in healthy individuals or patients with other neurological conditions.

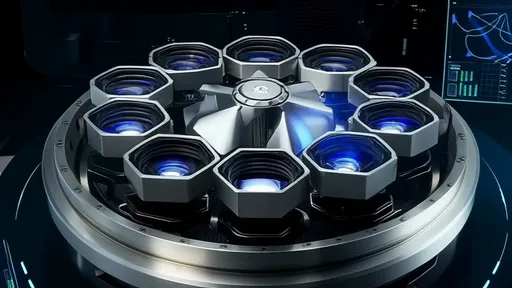

Recent studies using high-speed infrared eye-tracking systems have quantified these deviations with remarkable accuracy. For example, people in the early stages of Parkinson’s often exhibit hypometric saccades—short, undershooting gaze shifts—or increased latency in initiating eye movements. These subtle deficits, invisible to the naked eye, can be captured and analyzed through specialized software, providing clinicians with objective data to support early diagnosis.

Clinical Applications and Challenges

Translating these research findings into clinical practice presents both opportunities and hurdles. On one hand, eye-tracking tests could be integrated into routine neurological exams, especially for high-risk populations such as those with a family history of Parkinson’s or REM sleep behavior disorder. The tests are relatively quick, taking less than 15 minutes, and require no physical contact, making them ideal for repeated monitoring over time.

However, standardization remains a challenge. Variations in testing protocols, equipment, and environmental conditions can affect results. Additionally, while eye movement abnormalities are sensitive markers, they are not entirely specific to Parkinson’s; similar patterns may occur in conditions like progressive supranuclear palsy or Huntington’s disease. Researchers are now working on machine learning algorithms to improve diagnostic specificity by analyzing complex combinations of eye movement parameters unique to Parkinson’s.

The Future of Early Intervention

If validated in large-scale longitudinal studies, eye-tracking could become a cornerstone of pre-symptomatic Parkinson’s detection. This would open doors to neuroprotective therapies at a stage when they might be most effective—potentially years before traditional diagnosis. Imagine a future where a simple eye test during a routine optometrist visit flags early neurological changes, prompting further evaluation and proactive treatment.

Beyond diagnosis, eye movement analysis might also help track disease progression and treatment response more precisely than current rating scales. As pharmacological and gene therapies targeting Parkinson’s continue to advance, having sensitive biomarkers like eye-tracking metrics will be crucial for testing their efficacy in clinical trials.

The road ahead requires collaboration between neuroscientists, engineers, and clinicians to refine this technology. But the potential is undeniable: what begins as a subtle flicker in the eyes may light the way toward defeating Parkinson’s before it fully takes hold.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025