The oceans are drowning in plastic. Every year, an estimated 14 million tons of plastic waste enter marine ecosystems, breaking down into insidious microplastics that infiltrate every level of the food chain. Traditional cleanup methods have proven woefully inadequate against this microscopic invasion. But now, scientists are turning to an unlikely ally in this battle – engineered viruses that mimic nature’s most efficient predators: bacteriophages.

The Plastic Pandemic

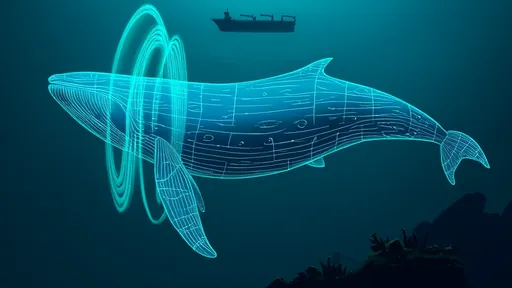

Microplastics, fragments smaller than 5mm, have become the environmental equivalent of cigarette smoke – ubiquitous, persistent, and toxic. These particles absorb pollutants like PCBs and DDT, becoming poison pills for marine life. When ingested, they cause internal abrasions, hormone disruption, and starvation in everything from plankton to whales. The problem compounds as these plastics move up the food chain, eventually reaching human dinner plates through seafood consumption.

Current solutions focus on prevention or mechanical removal, both facing significant limitations. Banning single-use plastics addresses future pollution but does nothing for existing waste. Ocean cleanup systems struggle to capture microplastics without harming marine life. This technological gap has driven researchers toward biological solutions – specifically, harnessing viruses that can break plastic down at the molecular level.

Nature’s Nanomachines

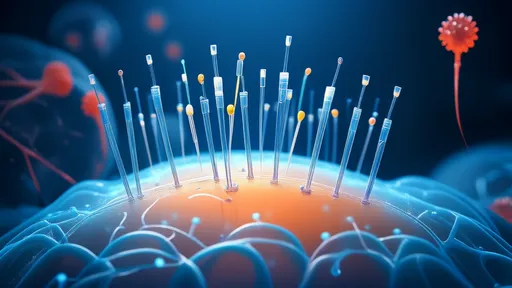

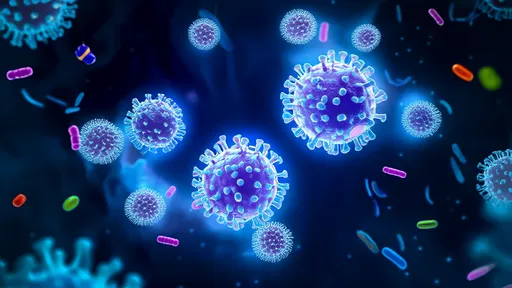

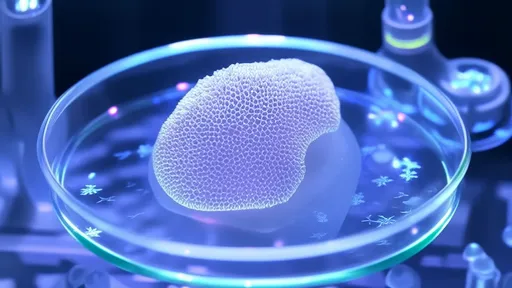

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, represent the most abundant biological entities on Earth. Their precision targeting and rapid replication make them ideal candidates for engineering. Scientists have modified these phages to produce plastic-degrading enzymes on their surface proteins. When these engineered viruses encounter microplastics, they latch on and begin breaking the polymer chains into harmless byproducts.

The approach mirrors how phages naturally attack bacteria. Just as wild phages inject genetic material to hijack cellular machinery, plastic-hunting phages deliver enzymes that dismantle synthetic polymers. Researchers have dubbed these modified viruses "plastiphages," drawing parallels to their bacterial counterparts while highlighting their new plastic-targeting function.

From Lab to Ocean

Early experiments show promise. In controlled seawater tanks, plastiphages reduced polyethylene and polypropylene concentrations by 47% over eight weeks. The viruses demonstrate remarkable specificity – they ignore biological material while aggressively breaking down common plastics. This selectivity could prevent ecological disruption if deployed at scale.

However, challenges remain before open-ocean deployment. Scientists must ensure the engineered viruses don’t transfer genes to natural microbes or mutate unpredictably. Current research focuses on "kill switches" that deactivate the phages after several generations. Another approach involves making the viruses dependent on synthetic amino acids not found in nature, creating a built-in expiration date.

Ecological Considerations

Marine biologists caution that introducing any engineered organism requires careful study of potential ripple effects. While plastiphages target synthetic polymers, their presence could still alter microbial communities. Some researchers propose contained use first – treating wastewater effluent where microplastics concentrate before entering oceans.

The decomposition process itself warrants scrutiny. Breaking plastics into smaller molecules doesn’t eliminate them; the end products must be truly biodegradable. Recent advances show certain enzymes can reduce plastics to basic organic compounds that marine organisms can metabolize, but achieving this consistently across plastic types remains difficult.

The Road Ahead

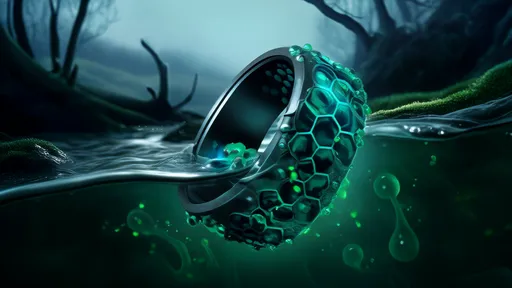

If these hurdles can be cleared, plastiphage technology could revolutionize marine cleanup. Unlike mechanical systems that struggle with microscopic particles, viruses operate at precisely the right scale. Their self-replicating nature means a small initial deployment could expand to address massive pollution volumes.

Several research consortia are racing to develop viable systems. The European Union’s Horizon program has invested €23 million in phage-based cleanup technology, while startups in California and Singapore are already prototyping delivery mechanisms – from slow-release capsules to drone-distributed viral "blooms."

This innovation comes not a moment too soon. Microplastic concentrations are doubling every decade in some marine regions. Without intervention, scientists project the total weight of ocean plastics will exceed all fish biomass by 2050. The plastiphage approach offers a glimmer of hope – harnessing nature’s own weapons to clean up humanity’s mess.

As research progresses, ethical questions will require as much attention as technical ones. How do we balance intervention risks against pollution consequences? Who governs deployment of engineered organisms in international waters? These discussions must happen in parallel with scientific development to ensure responsible innovation.

The seas have borne the brunt of human carelessness for generations. Now, cutting-edge science might provide tools to begin making amends – one microscopic plastic predator at a time.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025