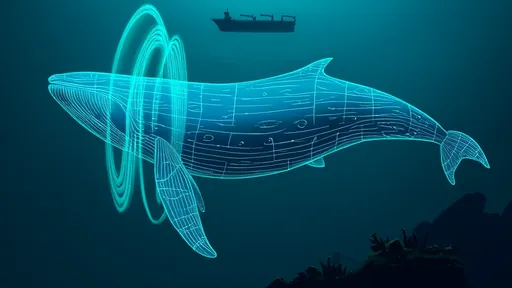

In a groundbreaking effort to protect marine life, scientists and engineers have developed an innovative acoustic barrier system inspired by whale communication. Dubbed the "Whale Song Moat," this technology leverages intelligent sonar arrays to create dynamic marine protected zones, effectively preventing unauthorized ship entry while minimizing harm to aquatic ecosystems. The system represents a rare convergence of bio-inspired engineering and conservation ethics, offering a non-invasive solution to the growing problem of human maritime encroachment.

The concept emerged from decades of research into cetacean vocalizations, particularly the hauntingly beautiful songs of humpback whales. Marine biologists had long noted how these complex acoustic signals travel vast distances underwater, forming a natural communication network across ocean basins. "Whales essentially navigate and socialize through sound," explains Dr. Samantha Reyes, lead bioacoustician at the Marine Conservation Institute. "Their songs can propagate hundreds of miles with remarkable clarity in the ocean's sound channels. We're borrowing that principle, but applying it as a gentle deterrent rather than a communication tool."

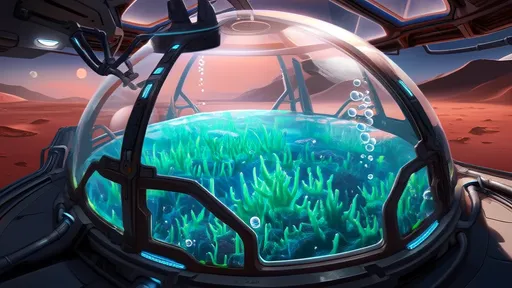

At the heart of the Whale Song Moat lies a grid of submerged acoustic nodes that emit precisely modulated low-frequency pulses. These aren't random noises, but carefully engineered soundscapes that mimic natural oceanic patterns while incorporating vessel-deterring signatures. The system's machine learning algorithms constantly adapt the acoustic output based on real-time marine traffic data, weather conditions, and even the presence of sensitive species. During whale migration seasons, for instance, the nodes automatically reduce output frequencies to avoid interference with actual cetacean communications.

What makes this approach revolutionary is its dual functionality. Traditional marine protected areas often rely on physical barriers or patrol boats - methods that are either ecologically disruptive or prohibitively expensive to maintain. The acoustic barrier creates an invisible, dynamic boundary that most ships' navigation systems recognize as an exclusion zone. Modern vessels equipped with standard AIS (Automatic Identification System) will receive automated alerts and course corrections when approaching the protected area. "It's like the ocean itself gently guides ships away," remarks naval architect Henrik Vollstad, who consulted on the project. "The sound waves don't damage vessels or marine life, but they form an unmistakable auditory boundary that maritime traffic instinctively avoids."

Early deployments have shown remarkable success in sensitive habitats. Off the coast of Chile, where blue whale feeding grounds overlap with busy shipping lanes, the system reduced unauthorized entries by 89% within six months of installation. Hydrophone recordings revealed that cetacean vocalization patterns became more stable and complex after implementation, suggesting reduced stress levels among local populations. Perhaps most encouragingly, the technology has proven effective against illegal fishing operations, whose vessels often disable AIS transponders but remain vulnerable to the acoustic barrier's deterrent effects.

The engineering challenges were substantial. Creating sound waves powerful enough to be detected by ships at distance, yet gentle enough to avoid harming delicate marine organisms, required breakthroughs in directional acoustics. Researchers developed phased-array transmitters that focus energy horizontally rather than vertically, preventing unnecessary depth penetration that could disturb deep-sea ecosystems. Each node operates at carefully calibrated frequencies between 30Hz and 1kHz - below most commercial sonar systems but within optimal range for ship detection. "It's a Goldilocks solution," says Dr. Reyes. "Too high and we risk interfering with dolphin echolocation. Too low and the signals become indistinguishable from natural ocean noise."

Environmental impact studies conducted over three years showed no measurable harm to plankton, fish larvae, or other sound-sensitive microorganisms. The system's intermittent pulse pattern - alternating between active transmission and quiet periods - allows marine life continuous opportunities to move through the area unimpeded. This stands in stark contrast to military-grade sonar systems, which have been linked to mass strandings of deep-diving cetaceans. "We designed the Whale Song Moat specifically to avoid such tragedies," emphasizes environmental engineer Luisa Moreno. "The waveform modulation follows principles of marine mammal vocal hygiene, with gradual ramp-ups and frequency variations that never approach harmful intensities."

Looking ahead, conservation groups envision global implementation across critical marine habitats. The Great Barrier Reef, the Galápagos Marine Reserve, and several Arctic migration corridors have been identified as priority deployment zones. Each installation would be custom-tuned to local ecological conditions, with sound profiles matching regional acoustic environments. In the Baltic Sea, for instance, where ice cover varies seasonally, the system would adjust transmission parameters to account for sound propagation differences between open water and ice-covered conditions.

Commercial shipping associations have cautiously welcomed the technology as a preferable alternative to outright navigation bans. "This gives us a way to protect sensitive areas without crippling maritime trade," says International Chamber of Shipping representative Gerald Fitzhugh. Early adopters include several major cruise lines whose routes intersect with whale habitats. By integrating the acoustic barrier data into their navigation systems, these companies can automatically reroute around protected zones while maintaining efficient voyage planning.

The Whale Song Moat represents more than just a technological achievement - it signals a philosophical shift in humanity's relationship with marine ecosystems. Instead of viewing protection as keeping nature separate from human activity, this approach allows for harmonious coexistence through intelligent design. As climate change and ocean industrialization accelerate, such innovations may determine whether critical marine species survive the Anthropocene. The ocean's ancient acoustic highways, first mapped by whales millions of years ago, now serve as blueprints for their own preservation.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025