The dense forests of Central Africa have long been a battleground between conservationists and poachers. While rangers patrol protected areas, illegal hunters slip through the shadows, leaving behind slaughtered elephants and pangolins. But a revolutionary forensic technique is turning the very air into an ally against wildlife crime.

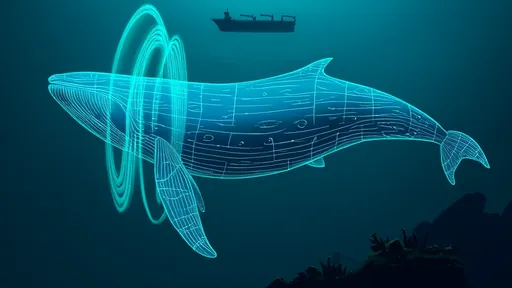

Scientists are now deploying environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling to detect the biological traces poachers leave behind in forest air. This cutting-edge approach analyzes genetic material suspended in airborne particles - skin cells, hair follicles, or even clothing fibers - to identify individuals who recently passed through an area. The method builds upon aquatic eDNA techniques used to track rare marine species, but applies the science to terrestrial crime scene investigation.

How does airborne genetic surveillance work? Research teams place portable air filtration units along animal trails and known poaching routes. These devices capture microscopic biological material that remains suspended in air currents for hours after human passage. Back in laboratories, forensic geneticists extract and sequence DNA fragments, comparing them against criminal databases or creating new genetic profiles of suspects.

The implications for wildlife protection are profound. Unlike camera traps that can be avoided or destroyed, air sampling stations are inconspicuous and collect evidence continuously. A single filtration unit can monitor a 200-meter radius, detecting multiple individuals who passed through the area within a 48-hour window. This creates what researchers call a "biological dragnet" - an invisible web that captures genetic evidence regardless of weather conditions or time of day.

Field tests in Gabon's Lopé National Park demonstrated the system's effectiveness. Air samples collected near fresh elephant carcasses contained human DNA that matched known poachers later arrested at nearby villages. In one case, genetic material recovered from a single air filter led authorities to three members of a commercial ivory smuggling ring.

Conservation geneticist Dr. Nalini Rao explains: "Every human leaves behind a cloud of genetic material as they move through the environment. We're essentially fingerprinting the air to see who's been present in protected areas where they don't belong." The technique has proven particularly valuable for distinguishing between local community members who gather forest products legally and armed poaching gangs.

Legal experts note that airborne DNA evidence must meet chain-of-custody standards to hold up in court. Proper documentation of sample collection, transportation, and laboratory analysis is crucial. Some jurisdictions are adapting forensic protocols originally developed for human DNA analysis to accommodate this new form of environmental evidence.

While promising, the technology faces challenges. Tropical downpours can dilute airborne genetic material, and the presence of abundant animal DNA sometimes makes human sequences harder to isolate. Researchers are developing specialized filtration membranes and more sensitive sequencing techniques to overcome these limitations.

Conservation organizations are already implementing eDNA monitoring networks in high-risk areas across Africa and Southeast Asia. The World Wildlife Fund recently trained ranger teams in five countries to operate air sampling equipment and preserve genetic evidence. This represents a significant shift from traditional tracking methods toward high-tech biological surveillance.

As the technique evolves, scientists envision expanding its applications. The same principles could help locate missing persons in wilderness areas or track the movements of endangered species. Some researchers suggest atmospheric DNA monitoring could eventually create real-time biological maps of protected areas.

For now, the focus remains on combating wildlife crime. With an estimated 35,000 elephants killed annually for their tusks, conservationists welcome any tool that might tip the scales. As one park warden in the Democratic Republic of Congo put it: "The forest remembers who walks through it. Now science can make that memory speak in court."

Ethical questions linger about genetic privacy and potential misuse of the technology. Civil liberties groups caution against creating DNA databases from environmental sampling without proper oversight. Conservationists counter that in crisis situations facing endangered species, extraordinary measures may be justified.

The development marks a new frontier in wildlife forensics - one where the air itself becomes a witness to crimes against nature. As poachers grow more sophisticated, so too must the methods to stop them. Environmental DNA analysis represents a powerful fusion of ecology and criminal investigation, turning the fundamental building blocks of life into tools for conservation.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025