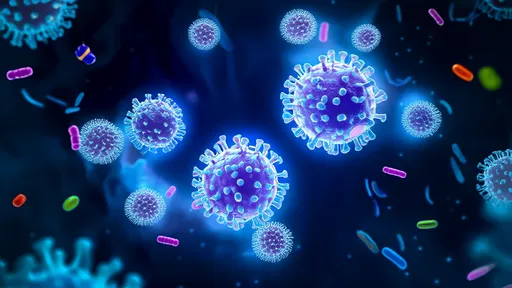

The world of fermented foods is a microbial wonderland, where invisible communities of bacteria and fungi work tirelessly to transform ordinary ingredients into nutritional powerhouses. For centuries, humans have harnessed these microscopic allies without fully understanding their complex ecosystems. Today, cutting-edge research is revealing how these microbial communities contribute not just to flavor and preservation, but to our overall health in surprising ways.

Walking into any kitchen where fermentation happens is like entering a living laboratory. The bubbling sauerkraut, tangy kefir, and earthy miso each contain distinct microbial profiles that scientists are only beginning to map. What makes this microbial mapping particularly fascinating is how these tiny organisms interact with our gut microbiome - that vast internal ecosystem that science increasingly links to everything from immunity to mental health.

The concept of a "microbial health index" for fermented foods represents a paradigm shift in how we evaluate these traditional foods. Rather than just counting probiotic strains, researchers are now looking at the complete microbial communities, their metabolic activity, and how they survive digestion to reach our intestines alive. This holistic approach reveals why some homemade ferments might outperform commercial probiotic supplements, despite having lower bacterial counts.

Take kimchi as a prime example. The Korean staple contains not just lactic acid bacteria, but an entire supporting cast of microbes that create the perfect environment for probiotic strains to thrive. Recent studies show that traditional kimchi preparations contain over 900 different microbial species working in concert. This microbial diversity appears crucial for both the fermentation process and the health benefits that follow.

What's particularly surprising is how these microbial communities evolve throughout the fermentation process. Early-stage fermentations tend to be dominated by fast-growing generalists, which then create the conditions for more specialized microbes to take over. This succession pattern mirrors what happens in natural ecosystems, and may explain why longer fermentation periods often yield more complex flavors and potentially greater health benefits.

The kitchen environment itself plays a fascinating role in shaping these microbial communities. Studies comparing identical fermentation recipes prepared in different homes show distinct microbial fingerprints based on the local environment. This helps explain why San Francisco sourdough tastes different from Parisian sourdough, and why generations of fermenters have guarded their "starter cultures" like family heirlooms.

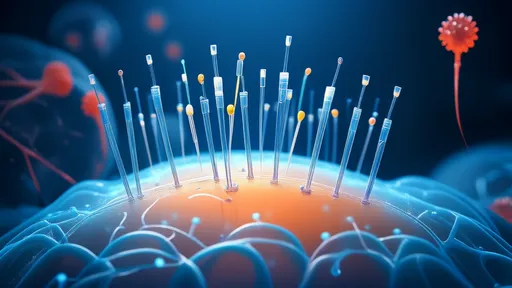

Modern sequencing technologies have allowed scientists to create detailed "microbial maps" of various fermented foods. These maps reveal that surface molds on aged cheeses communicate with subsurface bacteria through chemical signals, or that the yeasts in sourdough bread form complex social networks. Understanding these relationships could help both home fermenters and commercial producers optimize their processes for both safety and quality.

Perhaps most importantly, this research is helping us understand how different fermented foods interact with our individual microbiomes. Early evidence suggests that people with certain gut microbial profiles may derive more benefit from specific types of fermented foods. This could eventually lead to personalized fermentation recommendations based on an individual's microbiome analysis.

The microbial health index doesn't just consider the quantity of beneficial microbes, but their viability through digestion, their metabolic activity in the gut, and their ability to support existing gut flora. This explains why some fermented foods with relatively low microbial counts can have outsized health effects - their microbial communities are particularly well-adapted to survive the journey and colonize effectively.

As we continue to explore this microscopic frontier, one thing becomes clear: our ancestors' fermentation practices were far more sophisticated than we realized. Those cloudy jars of bubbling vegetables weren't just preserving food - they were cultivating complex ecosystems that modern science is only beginning to appreciate. The microbial map of fermented foods is still being drawn, but each new discovery reinforces the wisdom of these ancient food traditions.

For home fermenters, this research validates what many have suspected all along - that those subtle variations in technique, timing, and environment create unique microbial profiles that can't be replicated industrially. The slight cloudiness in homemade kombucha, the irregular bubbles in wild-fermented pickles - these are signs of a thriving microbial community that no laboratory could hope to duplicate precisely.

Looking ahead, the microbial mapping of fermented foods promises to revolutionize both small-scale and industrial fermentation practices. Imagine being able to test your sauerkraut's microbial profile with a smartphone app, or receiving personalized fermentation recipes based on your gut microbiome. This isn't science fiction - prototypes of such technologies already exist in research labs.

The implications extend beyond personal health to global food security. As climate change threatens traditional agriculture, fermented foods offer a resilient, low-energy method of food preservation and nutrition enhancement. Understanding their microbial ecosystems could help communities worldwide develop fermentation practices tailored to their local ingredients and conditions.

What began as a method to preserve surplus harvests has evolved into one of the most exciting frontiers in nutritional science. The humble microbial communities in our fermented foods represent a perfect symbiosis between human culture and natural processes - a reminder that some of our most important health allies are too small to see, but too powerful to ignore.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025