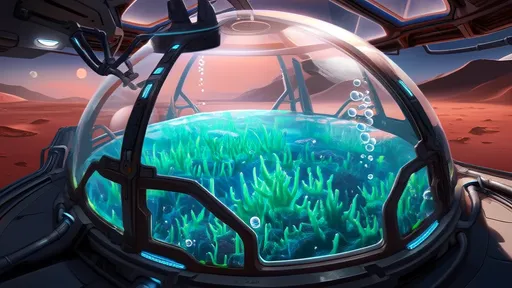

The quadrangle of Greenfield University buzzed with excitement last weekend as teams of environmental science students unveiled their miniature ecosystems for the annual Water Purification Challenge. This year's theme, "Constructed Wetlands: Nature's Filter," pushed participants to design scaled-down versions of artificial wetlands capable of cleaning contaminated water through natural processes.

Professor Eleanor Waters, chair of the Environmental Studies Department, explained that the competition serves as both a hands-on learning experience and a testing ground for sustainable water treatment solutions. "What these students are creating isn't just academic exercise," she said, kneeling beside an elaborate setup of aquatic plants and gravel filters. "These microsystems demonstrate principles being implemented in full-scale wetland projects across the country."

Twelve teams spent eight weeks designing their wetland systems, each taking different approaches to biomimicry. The designs ranged from simple gravel-and-reed setups to complex multi-chamber systems incorporating microbial communities. Common materials included recycled plastic containers, locally sourced wetland plants, and repurposed aquarium equipment.

The judging panel, comprising faculty members and water treatment professionals, evaluated the systems based on efficiency, innovation, cost-effectiveness, and educational value. Team AquaPhoenix drew particular attention with their vertical wetland design that processed contaminated water 37% faster than traditional horizontal layouts. "We noticed how mangrove roots work in nature," explained chemistry major Rafael Ortiz, "and we tried to recreate that vertical filtration space in our design."

Meanwhile, Team BioFiltr8 incorporated biochar produced from campus food waste into their substrate mixture, demonstrating impressive heavy metal removal rates. Environmental engineering student Priya Chatterjee noted, "The porous structure of biochar provides incredible surface area for microbial colonization while sequestering carbon - it's a win-win solution."

Perhaps the most striking demonstration came from Team EcoSynergy, whose system not only purified water but created habitat for amphibian life. Their carefully balanced ecosystem included duckweed for nutrient absorption, freshwater mussels for particulate filtration, and even a population of tadpoles as biological indicators. "The tadpoles are our canaries in the coal mine," joked team leader Marcus Yang. "If they thrive, we know the water quality is good."

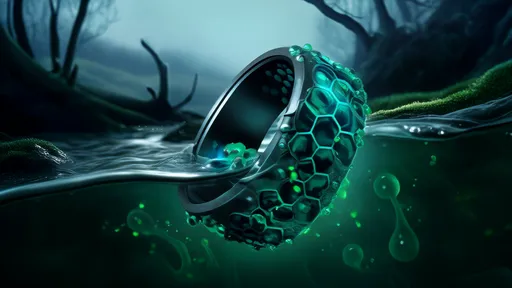

The competition's practical significance became clear during the stress tests, where systems had to process samples of water contaminated with motor oil, fertilizers, and household chemicals. Many spectators were surprised to see the relatively simple systems outperform conventional chemical treatments in removing certain pollutants. Dr. Waters emphasized this point: "What these students are proving is that sometimes the lowest-tech solution can be the most elegant and sustainable answer to pollution."

Beyond the technical achievements, the event served as a powerful educational tool. Hundreds of non-science majors stopped to examine the displays, with many expressing surprise at how effectively natural systems can address water quality issues. "I had no idea cattails could pull heavy metals out of water," remarked literature major Jessica Monroe, examining Team PhytoClean's dense stand of Typha plants.

The university plans to implement the winning design - Team ClearFlow's solar-aerated wetland system - as part of the campus stormwater management program. Their innovative use of passive solar panels to increase microbial activity during colder months particularly impressed the judges. "This isn't just a class project anymore," said a beaming ClearFlow member Sarah Kintner. "Knowing our design will actually help manage runoff on campus makes all those late nights totally worth it."

As the competition wrapped up, organizers noted growing interest from municipal water authorities and environmental nonprofits. Several representatives attended this year's event, looking to adapt student innovations for community water projects. "The creativity here is remarkable," observed Michael Trent from the State Water Resources Board. "We're seeing solutions that could be implemented in developing communities at very low cost."

The success of this year's competition has already inspired plans for expansion. Next year's event will include categories for middle and high school students, along with a new "urban wetland" challenge focusing on stormwater management in city environments. As Professor Waters concluded while awarding the trophies, "These students aren't just learning about environmental solutions - they're creating them. And that gives me tremendous hope for the future."

For those who missed the live event, the wetland systems remain on display in the Science Center atrium through the end of the month, with team members available to explain their designs during scheduled demonstration hours. The university has also published detailed project reports and design specifications online, hoping to inspire similar initiatives at other institutions.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025