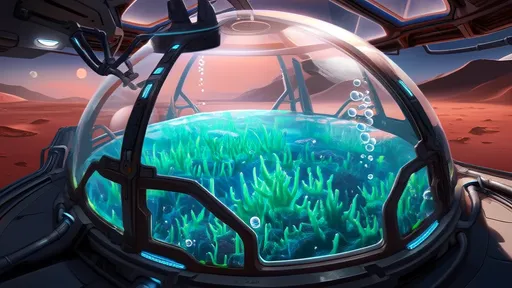

The concept of a "Cyanobacteria Oxygen Bar" on Mars may sound like science fiction, but recent advancements in bioengineering and space agriculture suggest it could become a cornerstone of future colonization efforts. Researchers are now focusing on pressurized domes housing nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria—often called blue-green algae—as a sustainable solution for producing breathable oxygen and stabilizing soil conditions in extraterrestrial environments. This innovative approach leverages Earth’s oldest photosynthetic organisms to tackle two critical challenges on the Red Planet: the absence of a nitrogen cycle and the thin, CO₂-heavy atmosphere.

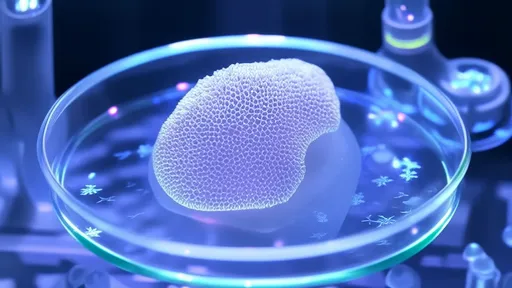

Under the translucent ceilings of these domes, cyanobacteria would thrive in carefully regulated conditions, converting Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide into oxygen while fixing nitrogen into bioavailable forms. Unlike traditional mechanical systems, which require constant energy input and maintenance, these living factories self-replicate and adapt to environmental fluctuations. Early experiments in simulated Martian habitats have shown promising results, with certain strains of Anabaena and Nostoc species demonstrating remarkable resilience to low pressure and high radiation when shielded by even thin layers of water or gel.

The implications extend beyond oxygen production. Cyanobacteria’s ability to break down Martian regolith and release trapped nitrates could revolutionize agriculture on the planet. By pre-processing the sterile soil within domes, these microorganisms would create a fertile foundation for higher plants—a vital step toward establishing closed-loop ecosystems. Some prototypes already integrate the algae with hydroponic systems, where their metabolic byproducts directly nourish crops like wheat and potatoes. This synergy reduces reliance on Earth-supplied fertilizers, a logistical bottleneck for long-term missions.

However, the technology faces significant hurdles. Contamination risks between dome compartments demand failproof biological containment systems, as an algal bloom in the wrong sector could destabilize gas ratios. Moreover, Martian dust storms—which can last months—pose a threat to dome transparency and, consequently, photosynthesis efficiency. Engineers are testing self-cleaning nanomaterials for dome surfaces, while astrobiologists work on genetically modified cyanobacteria strains that enter dormancy during prolonged light deprivation.

Ethical debates have emerged alongside the science. Some argue that introducing Earth organisms to Mars, even in controlled environments, constitutes a form of interplanetary pollution that could compromise the search for native Martian life. Proponents counter that the extremophile nature of cyanobacteria makes them likely candidates for panspermia theories anyway—and that survival demands pragmatic solutions. Regulatory frameworks for extraterrestrial bioengineering remain uncharted territory, though space agencies have begun drafting preliminary guidelines.

What makes the cyanobacteria approach unique is its scalability. A single dome covering one hectare could theoretically support oxygen needs for a dozen colonists while processing tonnes of regolith annually. Unlike electrolysis-based systems that split Martian water reserves, the algae require minimal liquid water—especially if engineered for hyper-arid tolerance. This aligns with the "light footprint" philosophy gaining traction among mission planners: using biology to minimize mechanical infrastructure and energy expenditure.

Field tests are imminent. The European Space Agency’s forthcoming Melissa project will trial a cyanobacteria-photobioreactor combo on the International Space Station, monitoring gas exchange rates under microgravity. Meanwhile, private ventures like MarsBio are developing modular dome units deployable by autonomous rovers ahead of human arrival. Their patented "algae tiles"—interlocking panels containing multiple cyanobacteria strains—aim to blanket future base perimeters as a living buffer against atmospheric leaks.

The psychological dimension shouldn’t be overlooked. Early Mars settlers will face unprecedented isolation in a stark, reddish environment. The presence of vibrant green-blue algal cultures under glass could provide visual relief and a tangible connection to terrestrial ecosystems. Some architects propose integrating the domes with communal spaces as "oxygen gardens," where colonists might tend algae cultures—a therapeutic routine counteracting the sterility of habitat modules.

As with all pioneering technologies, the timeline remains fluid. Conservative estimates suggest operational cyanobacteria domes won’t appear until the 2040s, contingent upon successful precursor missions. Yet the accelerating pace of synthetic biology and materials science could compress that schedule dramatically. One thing is certain: the humble cyanobacterium, having shaped Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago, may soon play a similar transformative role on another world.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025