In the face of escalating climate change, scientists are turning to nature’s own carbon-capturing powerhouses—mangrove forests. These coastal ecosystems have long been celebrated for their ability to sequester carbon at rates far surpassing terrestrial forests. Now, groundbreaking research into the genetic editing of mangrove "super roots" promises to amplify their carbon-storing potential, offering a potential game-changer in the fight against global warming.

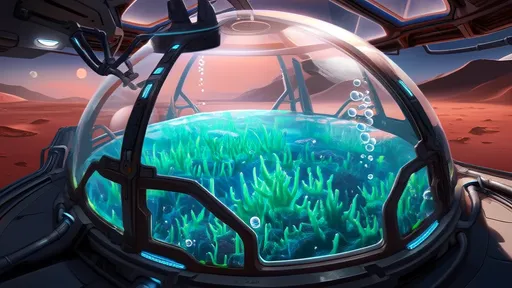

Mangroves thrive in the harsh, saline environments where few other plants can survive. Their intricate root systems not only stabilize coastlines but also act as biological carbon sinks, trapping organic matter in oxygen-poor soils where decomposition is slow. This results in carbon being locked away for centuries, if not millennia. Recent studies estimate that mangroves store up to four times more carbon per hectare than tropical rainforests. Yet, as rising sea levels and deforestation threaten these ecosystems, researchers are exploring how genetic engineering could bolster their resilience and efficiency.

The focus on mangrove roots stems from their unique adaptations. Unlike typical tree roots, mangroves develop specialized structures—pneumatophores—that rise above the waterlogged soil to absorb oxygen. These roots also excrete excess salt and host symbiotic fungi that enhance nutrient uptake. By identifying and editing key genes responsible for these traits, scientists aim to create "super roots" capable of faster growth, deeper soil penetration, and even greater carbon sequestration. Early lab experiments with CRISPR-Cas9 technology have shown promising results, with modified roots exhibiting a 20-30% increase in biomass production under controlled conditions.

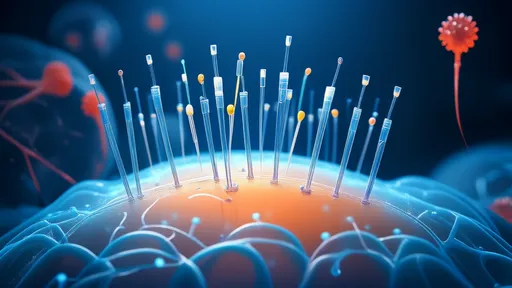

Dr. Elena Vazquez, a marine biologist leading one such project at the Singapore-based Blue Carbon Institute, explains: "We’re not trying to redesign mangroves from scratch. Instead, we’re amplifying what evolution has already perfected. A small genetic tweak to enhance root density or salt tolerance could translate into exponentially higher carbon storage across entire wetland systems." Her team’s work targets the SCARECROW gene family, known to regulate root development in plants. When overexpressed in black mangroves (Avicennia germinans), trial specimens developed thicker root networks with more lateral branching—ideal traits for trapping sediment and organic carbon.

However, the path from lab to coastline is fraught with ecological and ethical considerations. Critics warn that genetically modified mangroves could outcompete native species or disrupt delicate intertidal food webs. "We’ve seen how invasive species can throw ecosystems off balance," cautions Dr. Rajiv Singh, an ecologist with the Mangrove Action Project. "While the carbon benefits are compelling, we need rigorous field trials to understand how these edited plants interact with crabs, fish, and migratory birds that depend on natural mangrove habitats."

Proponents counter that time is a luxury climate change won’t afford us. Traditional mangrove restoration projects often struggle with low survival rates, sometimes below 20%. Gene-edited varieties engineered for higher stress tolerance could reverse decades of wetland loss more effectively. Pilot projects in Indonesia’s sinking deltas—where subsidence and saltwater intrusion have devastated coastal forests—are already testing salt-resistant mangrove saplings. Preliminary data suggests these plants establish root systems 40% faster than conventional seedlings, crucial for stabilizing eroding shorelines.

The economic implications are equally transformative. Blue carbon credits—tradable certificates representing carbon stored in coastal ecosystems—are gaining traction in voluntary markets. A hectare of enhanced mangroves could generate $3,000-$5,000 annually in carbon revenue for coastal communities, according to World Bank estimates. This financial incentive aligns conservation with poverty alleviation, particularly in developing nations where 90% of mangroves exist. "It’s not just about science," notes climate economist Dr. Hideo Takahashi. "We’re creating a model where protecting nature becomes more profitable than destroying it."

As the research advances, regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace. No international consensus yet exists on releasing gene-edited marine plants, though the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity has flagged mangrove modification as a "high-priority oversight gap." Meanwhile, biotech firms are patenting edited mangrove strains, raising concerns about corporate control over a resource critical to global climate stability. "These technologies should remain open-source," argues environmental lawyer Maria Fernandez. "Mangroves are a planetary commons—their enhancement must benefit all, not become another extractive industry."

On the ground, the technology’s success may hinge on local engagement. In Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, farmers who once cleared mangroves for shrimp ponds now participate in "carbon farming" cooperatives. Community-led nurseries propagate both traditional and edited varieties, blending ancient knowledge with cutting-edge science. "The trees protect our land from storms," says fisherman-turned-conservationist Le Van Bao. "If scientists can make them stronger, we’ll plant them by the millions."

Looking ahead, the vision extends beyond carbon. Supercharged mangrove roots might one day filter agricultural runoff, break down ocean plastics through symbiotic bacteria, or even produce biofuel precursors without competing for arable land. For now, researchers emphasize cautious optimism. As Dr. Vazquez puts it: "We’re not claiming this is a silver bullet. But in the mosaic of climate solutions, giving nature smarter tools could be our wisest investment."

The coming decade will test whether genetic engineering can safely amplify one of Earth’s most effective climate regulators. As greenhouse gas concentrations hit record highs, these twisted, salt-encrusted forests—and the scientists rewiring their very roots—may quietly hold a key to our planet’s fevered future.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025